Introduction

Nigerians are spending more on food than ever before. Every trip to the market feels heavier on the pocket — from rice to beans, the cost of daily staples keeps climbing.

This 2025 update breaks down what’s driving food prices across Nigeria right now. Backed by data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) and spot checks from Naijahfresh, it shows the real numbers behind your weekly shopping bill.

Ready to see how much food really costs in 2025? Let’s get into it.

Nigeria’s food price trend in 2025

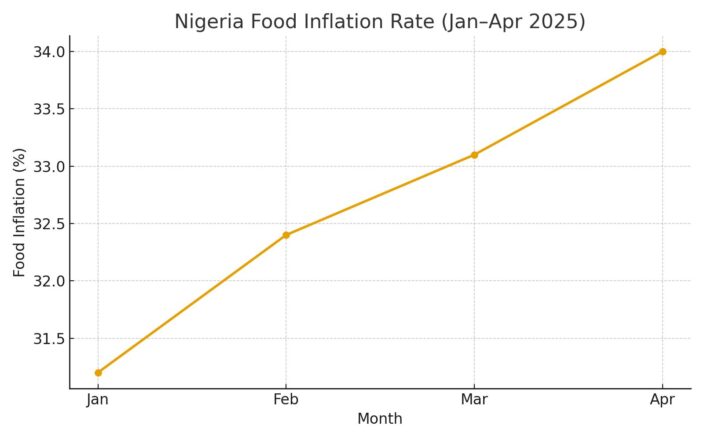

Food inflation in Nigeria has shown no sign of cooling. By April 2025, NBS reported a year-on-year increase of roughly 34 per cent, fuelled by the naira’s depreciation, high transport costs, and insecurity in key farming zones.

The sharpest jumps were seen in rice, beans, and edible oils — staples in nearly every home. Grains alone accounted for more than a third of the total rise in food inflation.

Here’s the hard truth: even when harvest seasons improve supply, logistics and currency pressures keep prices high. Analysts expect the trend to persist into early 2026 unless fuel and exchange rates stabilise.

Average food prices by category (October 2025)

The tables below combine verified NBS averages (April 2025) with Naijahfresh retail prices (October 2025) converted at ₦1,900 / £. They reflect what most Nigerians are paying at the market — and what diaspora buyers see online.

Grains and cereals

| Item | Unit | NBS Avg (Nov 2025) | Naijahfresh (Nov 2025) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice (local) | 1 painter | ₦8,160 | ₦5,000 | High due to transport and milling costs |

| Rice (50 kg bag) | 1 bag | ₦89,000 | ₦80,300 | +24% vs 2024 |

| Maize (white) | 1 painter | ₦3,000 | ₦2,900 | Driven by poultry-feed demand |

Insight: Rice remains the biggest strain on household budgets. Even locally milled rice now competes with imported brands in price, thanks to energy costs and unstable supply.

Beans and legumes

| Item | Unit | NBS Avg (Apr 2025) | Naijahfresh (Oct 2025) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beans (brown) | 1 painter | — | ₦4,200 (≈ 5 kg) | Premium staple; storage issues push cost |

| Fiofio (pigeon pea) | 1 painter | — | ₦6,300 | Local alternative to beans; price climbing |

| Iron beans | 1 painter | — | ₦4,000 | Speciality variant; scarce supply |

What’s happening: Bean prices refuse to cool. Storage losses and regional demand from neighbouring countries keep pushing them up.

Tubers and cassava products

| Item | Unit | NBS Avg (Apr 2025) | Naijahfresh (Oct 2025) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yam tuber | 1 piece | ₦6,200 | ₦8,000 | Retail average still ₦1,200 – ₦1,400 |

| Garri (white) | 1 painter | ₦1300 | ₦1,700 | Slight relief since mid-2024 |

| Achicha (dried cocoyam flakes) | 1 painter | — | ₦3,200 | Niche product; regional favourite |

| Cocoyam (ede ofe) | 1 painter | — | ₦4,200 | Seasonal; often substitutes yam |

Garri’s price is finally stable after a year of volatility — but don’t expect a return to pre-2023 levels anytime soon.

Cooking oils and fats

| Item | Average Price (₦) | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Palm oil (1L) | ₦2,300 | Per litre |

| Vegetable oil (1L) | ₦3,600 | Per litre |

Comment:

Palm oil prices are up, driven by export demand and packaging costs.

Proteins (fish, eggs, meat)

| Item | Average Price (₦) | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Frozen fish (1kg) | ₦4,700 | Per kg |

| Egg (1 crate) | ₦7,000 | Crate |

| Beef (boneless, 1kg) | ₦7,200 | Per kg |

Add note:

Protein foods are rising fastest among urban households due to feed and energy costs.

Fruits and vegetables

| Item | Average Price (₦) | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Tomatoes (1 paint) | ₦6,500 | Painter |

| Onions (1kg) | ₦7,200 | Per kg |

| Plantain (1kg) | ₦7,000 | Per kg |

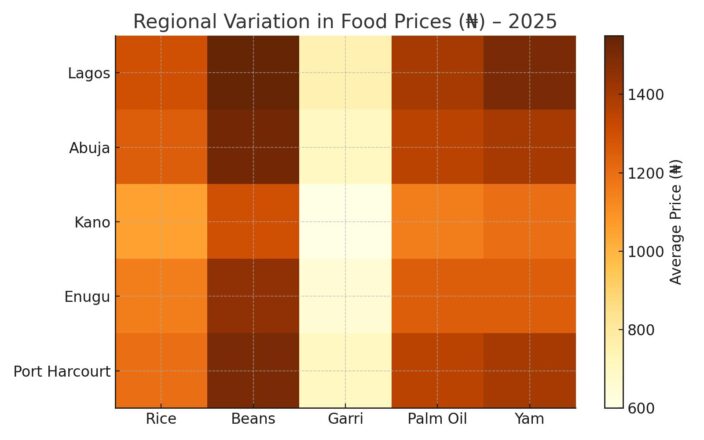

Regional price comparison

Food prices vary widely across Nigeria.

While Lagos and Abuja continue to record the highest retail costs, cities like Kano, Oyo, and Enugu enjoy slightly lower prices thanks to proximity to farms and cheaper logistics.

| Region | Rice (1 painter) | Beans (1 painter) | Garri (1 painter) | Palm oil (1 L) | Yam (1 piece) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lagos | ₦8,000 | ₦5,550 | ₦2350 | ₦2400 | ₦7,500 |

| Abuja (FCT) | ₦7,250 | ₦5,520 | ₦2400 | ₦2,550 | ₦8,400 |

| Kano | ₦6,050 | ₦4,300 | ₦1600 | ₦2,150 | ₦6,200 |

| Enugu | ₦7,150 | ₦1,450 | ₦1850 | ₦2,250 | ₦7,250 |

| Port Harcourt | ₦8,200 | ₦5,250 | ₦2000 | ₦2,350 | ₦8,400 |

(Figures combine NBS regional averages and Naijahfresh spot-checks.)

Lagos tops nearly every category, mostly because of transportation and rent costs. Northern states benefit from proximity to farms but still face price surges whenever fuel or fertiliser costs rise.

What’s driving the price changes?

Nigeria’s food prices don’t climb by accident.

Here’s what’s really going on behind the numbers:

Fuel and transport costs

Fuel remains the single biggest cost driver. Since January 2025, the average pump price of petrol has hovered around ₦680 per litre. Every trip from Kano to Lagos adds thousands in transport cost to a single truckload of rice. That burden filters straight to the end-consumer.

Exchange-rate swings

With the naira trading around ₦1,900 to £1 (or ₦1,600 to $1), the cost of imported fertilisers and packaging materials has exploded. Even locally grown foods aren’t spared — mills and processors import spare parts, diesel, and packaging inputs in foreign currency.

Insecurity in farming regions

The North remains Nigeria’s breadbasket, yet violence and displacement have cut farm output by as much as 30% in some zones. Many farmers now pay “security levies” just to access their fields — and those costs show up in retail pricing.

Storage losses

Nigeria loses about 40% of perishable crops before they reach markets (FAO, 2024). Poor warehousing and lack of cold-chain systems mean that even bumper harvests can’t guarantee cheaper prices.

Speculation and middlemen markup

Speculators hoard grains when they expect shortages, tightening supply and raising prices artificially. This cycle repeats almost every quarter, especially before major holidays when demand spikes.

Bottom line: The real inflation doesn’t start in the market — it starts on the road, in the fuel tank, and at the farm gate.

Bottom line: even when farmers harvest enough, getting food safely to market is what drives the bill higher.

How Nigerians are coping

Nigeria’s food inflation crisis has forced creativity at every income level.

Here’s how people are fighting back:

Bulk buying and group sharing

Middle-income households now pool funds to buy a bag of rice or beans, splitting it among neighbours. This co-operative shopping trend is booming in urban estates and university communities.

Local substitutes over imports

Dishes that once relied on imported rice or spaghetti now feature sorghum, acha, or yam flour. Traditional grains are making a comeback — not out of nostalgia, but necessity.

Smarter preservation

With power supply unreliable, many now sun-dry tomatoes, crayfish, and peppers to stretch shelf life. Market women even rent solar dryers to reduce spoilage.

Budget tracking and price awareness

The internet has changed the game. Nigerians now follow NBS and Naijahfresh updates before shopping — turning what used to be guesswork into informed budgeting.

Community resilience

Inflation has quietly revived age-old habits of food sharing and exchange. From “bring one tuber, take one derica” in villages to shared pantry groups in cities, solidarity is keeping people fed.

Every adjustment tells the same story — Nigerians may not control the economy, but they’re mastering adaptation.

These small moves add up — and they show the resilience of Nigerian households under inflation pressure.

Key takeaways (October 2025)

| Metric | Insight |

|---|---|

| Food inflation | ~34 % year-on-year (NBS 2025) |

| Most expensive staples | Beans, rice, and cooking oil |

| Most stable items | Garri and yam |

| Highest-cost cities | Lagos and Abuja |

| Primary cost driver | Fuel and logistics |

| Emerging trend | Rise of co-operative shopping and local substitutions |

Nigeria’s 2025 food story is one of pressure — and persistence. The data shows the strain, but the adaptation shows the strength.